VII. A LIFE AS A CRAFTSMAN AND DESIGNER OF LIVING SPACES

Houses, apartments, gardens

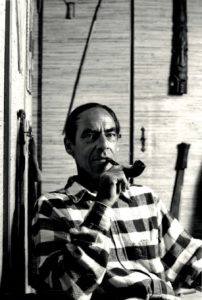

Even if the love of literature took me to foreign spheres, I remained a practical-minded person all my life, hard-working but without ambition; I was indeed a restless spirit, always seeking the wide, the deep, the unknown and the gripping “with the soul”, but I was never satisfied with what I had achieved and would not have known what I should actually have been proud of.

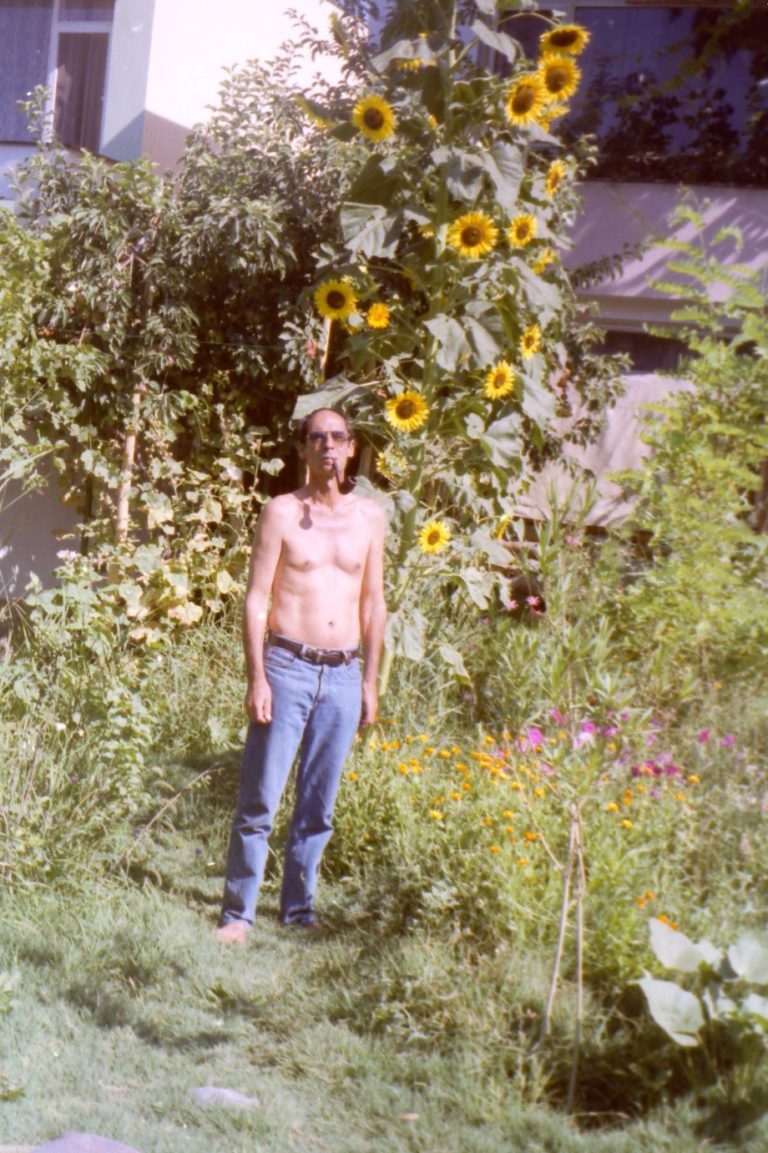

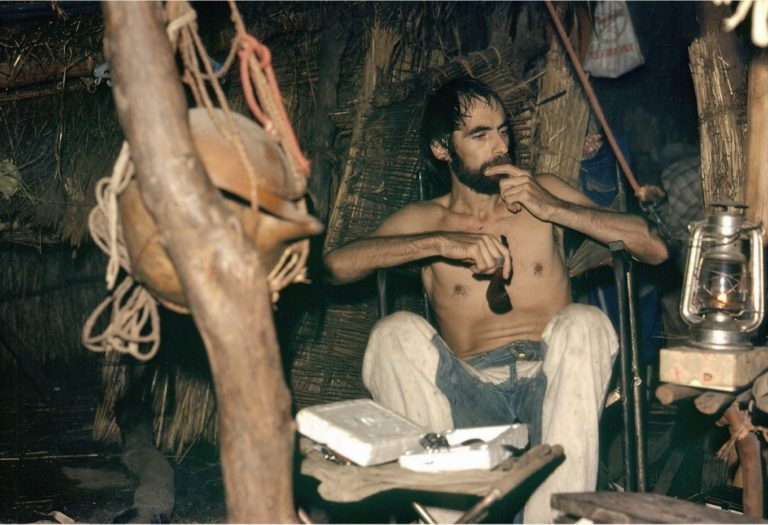

Sometimes I think I lacked self-confidence and the ability to be satisfied with my work. I could only be really satisfied when I could see and touch the results of my work. This was especially the case when building huts (during primary school and much later in South Sudan) or designing the interiors of flats and houses (in Davos, in Geneva with Andreas Auer), setting up delegations (in the Nuba Mountains, in Yirol, Ler and Pochalla in South Sudan and in Dolisie in Congo-Brazzaville), or gardening wherever I lived and where there was room for a garden.

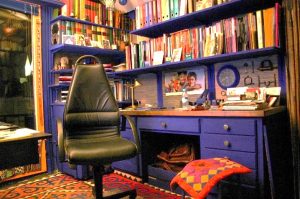

I did the most work in the house of my ancestors in Davos. German archaeologist and photographer Klaus Powroznik has created a 3D documentation of the house (see https://www.musethno.uzh.ch/static/perner/), but the documentation, as detailed as it is, only shows the current, modern condition but not the work I had done over the years, mostly without any help. The documentation, however, gives an idea of what was important to me: to create an atmosphere where the various elements do not become visible as individual parts and stand in the centre of attention, but rather come together through an interplay to create an overall impression.

Colours (every room has a different colour!), carpets and different materials (wood, bamboo, grass, different coloured wallpapers) are supporting elements of these facilities; they lead the visitor into ever new, differently designed rooms, with many large mirrors giving a feeling of space and enlarging the rooms.

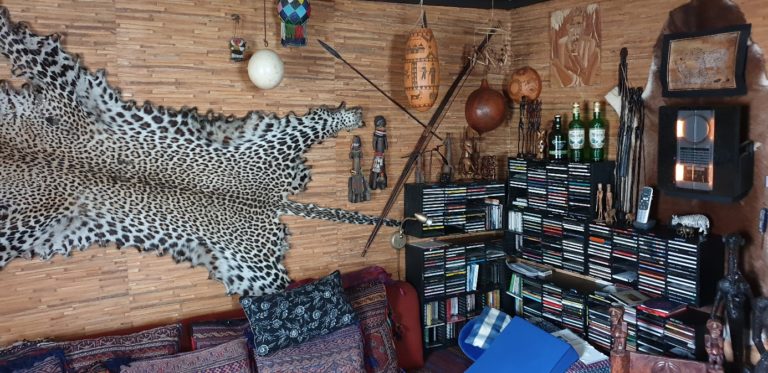

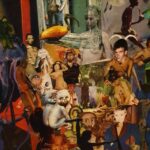

The interior consists of carpets (mostly Kilims from Afghanistan) and textiles, bookshelves filled to bursting, chairs of various shapes, wooden or iron sculptures, dolls, oil lamps, spears and necklaces and countless other objects of ethnographic significance, painted pictures and photographs. The aim of my work was to take the exhibited objects out of the focus of the guests and put them in the background, to open up the spaces. The visitors should not feel constricted, but be able to enjoy themselves in peace. The fireplace and not too intrusive and loud music in the background (for example the playing of the Tunisian musician Anouar Brahim) are further elements that should give the guests a pleasant feeling of relaxation and well-being.

In the house there are also various musical instruments (such as Nilotic guitars, tam-tam, drums, sanza, etc.), but I myself love music of all kinds (yodelling included!), but I am completely non-musical – except when listening. So, I have not been much involved with music, except during my student days (I did a three-quarter hour programme of Swedish chansons for Radio Beromünster) and during my fieldwork in Southern Sudan (recordings are on a CD in the monograph on the Anyuak). Music has always been an extremely important part of my life, even as a concert-goer; only during my ethnographic research did I not listen to music – that of drum dances and occasional guitar playing excepted.

An overview (without the accompanying pictures) of the history of the house and the objects in it can be read here:

Objects of value I hardly own; a few paintings by African painters and some statues created from scrap iron by a Ugandan artist may be of interest to art collectors, but practically all the other objects are only of ethnographic significance and impress only by their simple beauty and sensual appeal. Thus my flat in Davos bears witness not only to my own visions, but above all to the creative power of craftsmen from foreign cultures.

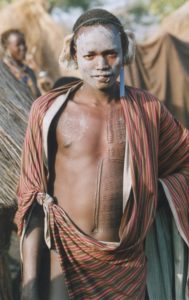

During my time as a researcher and then as a peace advisor to Switzerland, I took a lot of photographs. So most of my photographs come from Africa, the vast majority from my time with the Anyuak people, with whom I lived for over five years. While the material documentation of my research work is kept in the ethnographic museum in Geneva, my photographic recordings (together with audio documents) from South Sudan are in the archives of the Ethnological Museum of the University of Zurich.

My grandfather was a passionate photographer and even invented a kind of “glasses” through which photographs could be seen in three dimensions. I myself started taking photographs only at the time of my research in South Sudan, and only because documenting life was part of my work. In Bangladesh, India, Vietnam and during my travels in Asia or in Africa, I also took photographs, but these photographs were not much more than souvenirs and thus only of personal significance. Although these pictures were mostly taken with mediocre cameras and are therefore not of good quality, I would not want to miss some of these photographs; they remind me not only of landscapes, but above all of the people I met during these times.

During my time as an ICRC delegate in Africa, it was forbidden to walk around with a camera, and I (unlike other delegates) respected this important rule. Documenting the suffering of others, whether wounded, trapped or starving, was in any case fundamentally abhorrent to me – I felt it was shameless and lacked respect for those very people helplessly exposed to their suffering. In retrospect, however, I regret that I was allowed to document so little of nature and the daily life of the inhabitants at that time – some of them would have been historically unique photographs. Only in Afghanistan and Central Asia was photography allowed by the ICRC, and so I took home many photographs from these countries that still touch me personally and are also historically interesting.

Because it had meanwhile become a habit for me, and because technical progress made the carrying of large cameras unnecessary, I also took photographs on occasion after my return to Switzerland, on the one hand at home (pictures of friends and guests) and on the other hand during my walks and excursions in the mountains. Again, these are just memories put on paper; the beauty of the pictures has less to do with me as the photographer than with the magnificent nature in the Davos landscape.

The photographs of landscapes and visitors are kept in more than ninety albums; but most visitors can also find themselves in the collages in the toilet on the third floor of the house.

(The copyright for the photographs shown on this homepage remains with me and Prof. Beckry Abdel-Magid of Winona State University in Minnesota/USA. For research, schools or other non-commercial purposes, the Ethnological Museum of the University of Zurich will provide copies of the photographs).

The three toilets, which are of course located outside the flat in the staircase, are also interesting for visitors: while the lowest toilet with its painted porcelain bowl, pictures and sketches bears witness to the last years of the 19th century (the beginnings of the spa town of Davos) and the work of my grandfather, the middle toilet is alive with many postcards with very different subjects.

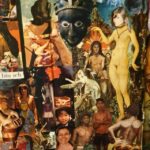

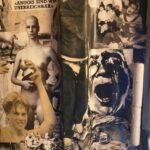

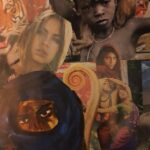

The third toilet, located between the second and third floors, is unique in many ways: it is small and narrow, but at the same time filled with photos of visitors, artists and newspaper cuttings. These collages of very different human faces have been enriched in content by a large number of quotations, from newspapers or poetry books, which bring depth and meaning to the collection of human faces.

I have written an introduction to the history of the creation of this much admired toilet:

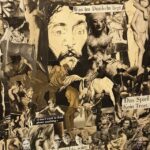

An old collage from 1968 (the time of the so-called Globus riots in Zurich) can also be found in the guest room; in contrast to the toilet, the texts here are of a rebellious essence, harder and more aggressive – quite in keeping with my youthful age as a student in Zurich.

The collages in the toilet, where all the walls, the ceiling, the floor, the door and the small window niche are covered with photos, consist mainly of pictures of visitors to the toilet, of relatives and friends who remain present here forever, – whether they have already passed away or have only returned to their places of residence. All these people have filled the house with life and given meaning to my own existence; without them, my efforts to make the living spaces beautiful would have been useless. Ultimately, it was my guests, not pictures, books and objects, who shaped the essence of the house and filled it with their spirit, enriching and enchanting it. “A guest is an angel sent to you by God” – this Arabic proverb has proven true again and again in my homes and gardens. My visitors have left lasting traces, not only of memory and in pictures, but also in my heart and in my daily life.

In Davos, but also in the arid Lokichokio in Kenya, in Pochalla in South Sudan or in Kabul in Afghanistan, my homes and especially my gardens became oases of peace, tranquillity, relaxation and friendship, whether they consisted of flowers, elephant grass, perennials, grapes, stones or cacti or were enlivened only by abstract drawings in the sand or by magical sculptures and fireplaces.