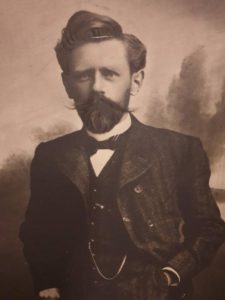

II. A LIFE AS AN ADVENTURER AND TRAVELLER

I spent my entire youth, until the end of my school years, in the mountains of Davos. Already as a child, I spent my free time outdoors, in the forests and valleys of our landscape, during the week with schoolmates and during the weekends with my sister, parents and neighbours. In the forests we boys built huts high in the fir trees, in the valleys we looked for anemones, blue or even yellow gentians, long-stemmed primroses in spring, alpine roses in summer and silver thistles and blueberries in autumn. We tied up the red alpine roses, which were not quite open yet, and sent them by express to relatives in the Unterland;

Flowers

only the old Mr Gensetter (he always brought us a 2.20m Christmas tree at Christmas) sold his bundles of alpine roses to departing Sunday guests at the railway station. When the weather was good, it was unthinkable for us to stay at home, and my father had little desire to “bloat on the promenade”, as he called the bourgeois Sunday stroll along the promenade.

So, the mountains, not the valley, became my physical and spiritual home from childhood; it was there that I felt at home, and it was probably there that I drew the strength I would need in abundance later in my life. I grew up in the mountains and that is where I learned to be courageous, fearless, confident, and yet also sensitive and cautious. The mountains were the measure of all things, they showed me not to overestimate my own possibilities, to be respectful and modest. The feeling of solidarity with other people was perhaps innate in me, but the mountains were the place where one felt physically connected to companions by a rope as I shared my own destiny with them.

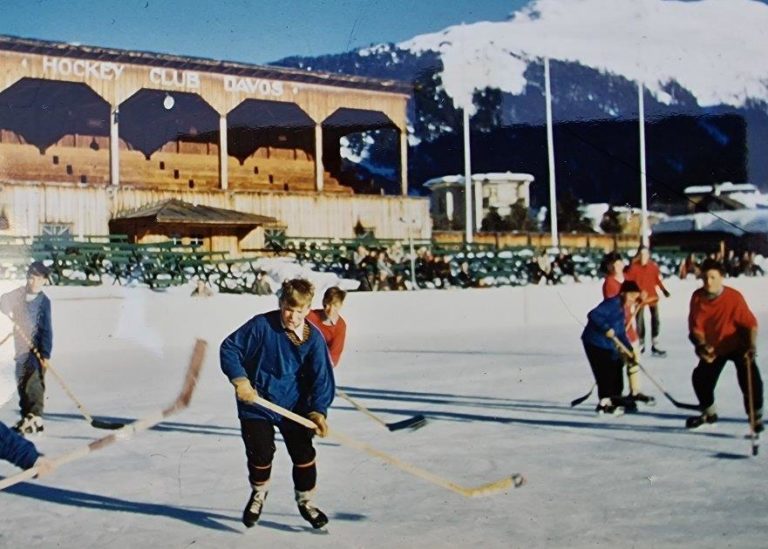

Our house was (and still is) in the centre of Davos, equidistant and only a few minutes away from the train station, the church, the primary and secondary schools, the Schatzalpbahn, the ice ring, the Bolgen ski lift and (today) the cross-country ski trail and the Brämabüelbahn (later renamed Jakobshornbahn).

During primary school I spent almost all my free time in winter on the ice ring but sledging on the icy toboggan run from the Schatzalp down into the valley was also one of my most exciting experiences back then.

At that time, Davos was the most important skating centre in the world, with a huge natural ice ring and an open hockey stadium: not only hockey games (only locals played at the Hockey Club Davos – HCD) were held here, but also European or World Championships in both figure skating and speed skating: since Davos (together with Alma Ata in Kazakhstan) had the fastest natural ice in the world, speed skaters from all over the world came here to train; daily spectacle was guaranteed. Because there was no television and few other events in Davos at that time, these competitions were attended by almost all the locals; the successes of the HCD boosted the self-confidence of the Davos people, and most of the boys dreamed of becoming hockey players one day. I played ice hockey at that time, of course, but after transferring to secondary school I was drawn to the snow and thus to the mountains;

with the school sports group, with the Alpine Club, with friends (such as Ottto Wild and Hans Wehrli) and with world-famous mountaineers such as the Reiss brothers, I climbed with sealskins on 2. 20m long ash-wood skis and enjoyed wonderful telemark descents in powder snow, in sulz or on firn – but sometimes also experienced terrifying adventures in steep glacier walls (Grialetsch) or in avalanches (Bärental with Cantate Issler and Fanez with Otto Wild). Every full moon, I and my friends were drawn to the brightly lit peaks at night, – sometimes for five consecutive nights! They were wonderful and always very happy days in the snow.

The mountains that tempted us to go ski touring in winter seemed too harmless and boring to climb in summer – with exceptions such as the distant Monte Disgrazia or the steep ascent of Piz Quattervals. At the age of fourteen I became a member of the Swiss Alpine Club (SAC) and immediately became a rope companion of many well-known alpinists, among them André Roch from Geneva, known for expeditions and countless first ascents in the Alps, who was then working at the Davos Avalanche Research Institute. With these much older and experienced rope companions, I climbed the various climbing mountains in the area at a young age, although the most daring and adventurous mountain tours were usually undertaken with my school friend Otto Wild.

André Roch also wrote mountain books (I translated his illustrated book “La Haute Route” from French into German) and made mountain films. When he asked me to go with him to the south of France to make a climbing film about me and the famous extreme climber Georges Livanos in the Calanques of Marseille, I had no idea that André’s film project would have professional consequences for my entire later professional life. After completing the (aborted) film project, I stayed in the south of France, climbed in Livanos’ exclusive small group of “Extremsti” and began a two-year study of French language and literature in Aix-en-Provence.

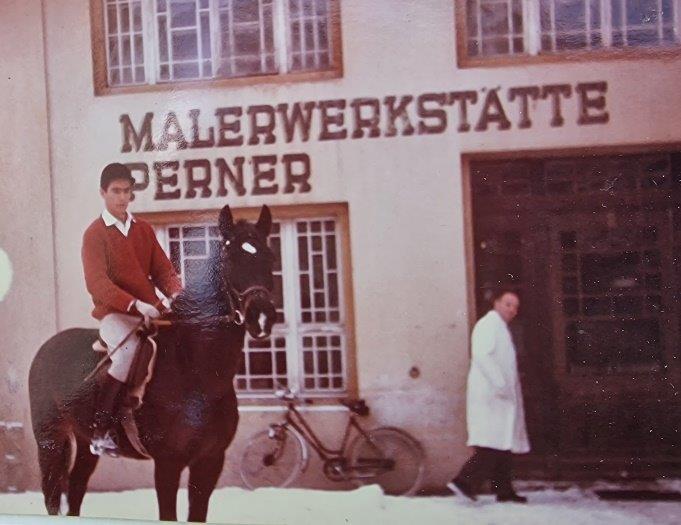

Thanks to the invitation of friends of my parents, I was allowed to learn to ride in Verden an der Aller in Germany; this was the beginning of another lifelong passion: the love of horses. I rode in Davos (with riding instructor Hans Lenz), in Maienfeld (with Bib Torriani and his family), in the English Garden in Munich and later also on red earth in the pine forests of Mount Sainte-Victoire near Aix-en-Provence and on the white horses of Camargue in France).

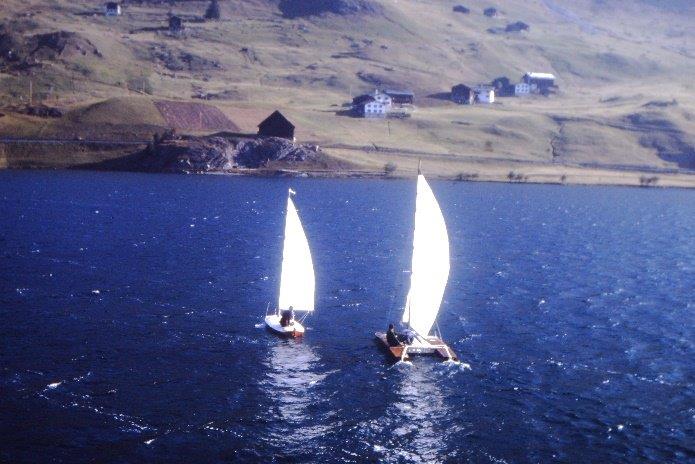

André Roch also had another passion besides the mountains: sailing. In my father’s workshop André made small and larg sailing boats (of the mot and catamaran type), which he then tried out on Lake Davos. I was allowed to sail with his son, my school friend Jean-François; I will never forget sailing in thick snowfall on the almost windless, silent lake of Davos, as well as a violent gust of wind that turned our catamaran upside down in seconds, with the mast vertically in the depths and us youngsters terrified in the ice-cold water. Unlike today, we didn’t see any sailing boats on Lake Davos back then.

With the army recruitment school (in the artillery) a new chapter in my life began, but the activities of youth still spilled over for a while into the time of studies. Soon travel and expeditions would come to the fore, but the experiences gained in my youth would also enable me to survive new adventures and dangers, gain new insights and discover myself in the process.

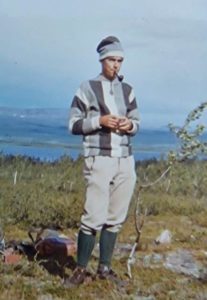

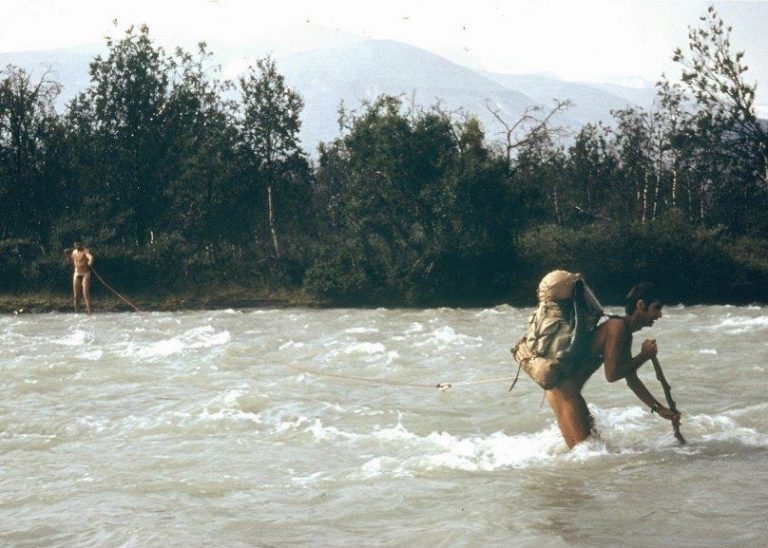

During my student days, I rarely returned home. Mountains remained my fondest memories of my youth, but now they receded into the far distance. New, tempting horizons opened up, first in Sweden, then in Africa and many other places. The first and only really adventurous expedition in Europe I undertook was in the Sarek region of Lapland: with two of my best school friends (Koala Spain Lumpur /Hans Wehrli) and Hanspeter Dänzer) I wanted to cross the then still untravelled, wild right side of the Rapa Valley, partly because there were bears there and partly because the great German storyteller Alfred Andersch had tried in vain to get through here and had almost died in the attempt. We didn’t succeed in this all too daring undertaking either, but at least we got away with the horror: while crossing the raging Rapa River, I was swept away by the powerful current and had actually already drowned when the avalanche cord my friends had secured me with pulled me back to the saving shore.

(My travel report with pictures by Hanspeter Dänzer still reminds of this expedition into the wilderness of Lapland).

During my work for the ICRC and my teaching at universities, there was little opportunity for longer excursions on foot. My colleagues at the ICRC felt little desire to accompany me on my expeditions, to visit far-flung cultural sites and to venture into inaccessible and inhospitable regions. So, I usually undertook such journeys on my own.

This was also the case in northern India, where – after visiting the golden temple of the Sikh in Amritsar – I decided to travel by bus to Dharamsala (the residence of the Dalai Lama and many refugees from Tibet) to climb the mountains of the Dhauladhar, the first high range of the Himalayas, which lie above the city. At high altitude, I spent three unforgettable days (and bitterly cold nights in a stone hut) in the company of petty shepherds and their mountain goats.

I also sought adventures on the island of Bali in Indonesia. After a few culturally very fascinating days in Denpasar, where I learned about the existence of three-metre tall and up to eighty kg man-eating giant lizards, I looked for possibilities to fly to Flores; Flores is one of only five small islands where these life-threatening lizards still live. At that time, the island was still undeveloped for tourists, there was no airfield and only one tiny little hostel. I was the only tourist. My wish to see the notorious Komodo dragons with my own eyes could not be fulfilled, because the boat that could have brought me close to the lizards only sailed once a month.

Nevertheless, the stay in Maumare, the capital of the island, was rewarding. A visit to the huge bustling market became a fascinating voyage of discovery into the colourful realm of exotic fruits, never-before-seen vegetables and fiery spices, spread out on the ground next to hand-woven textiles, dyed hemp ropes and forged tools. Closely associated with Flores is also the memory of an extremely bumpy ride in a jeep (past a village that was located on a steep slope and was probably called “Rock and Roll” for that reason), which brought me close to a volcano. The long climb up the volcano was worth it, because from the height you got a view of three craters, all filled with water: one of these three lakes was saffron yellow, one turquoise and the third rust red!

It was a breathtaking sight. I did not stay long enough to witness that after a certain time the lakes change colour and apparently turn green, brown or even black… High up on the volcano, a man dressed only in a loincloth suddenly appeared, holding a huge shooting bow and a long arrow. The spectacle of the Kulimutu volcanic lakes was magnificent and beguiling to the senses, but the inexplicable appearance of the man in the dead wasteland at the height of the volcano gave the spectacle something mystical and at the same time somewhat surreal. We sat down on the ground, gazing dreamily at the coloured lakes.

Who was the man, and why did he give me his bow and arrow as a parting gift? Was it because we couldn’t talk to each other or otherwise exchange ideas in any way? Questions upon questions… But that big bow and arrow has been hanging in my living room in Davos since that visit, giving my memory it’s still inexplicable meaning.

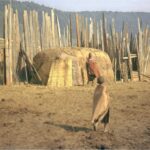

The marches (in total far more than 1000km long) were described in detail in the book “Why Did You Come If You Leave Again?“, especially the adventurous marches from Pibor to Otalo, from Otalo to Akobo, from the Boma Plateau down to the Akobo River to Otalo, or the forced march during the rainy season from Pochalla to Pibor and further to Bor.

TRAVEL TO A FOREIGN LANDS

My grandfather walked from Kuden in the north of Schleswig in Germany to Constantinople and Jerusalem (suffering from tuberculosis, he went to Davos and settled there). Those were times when you could only expand your horizons on foot or on horseback. In my youth, you could at least travel by train, then by car (we didn’t have one) and finally you could even fly through the air in planes.

When you think back to experiences in distant parts of the world, it is easy to forget how arduous and dangerous it often was to get to your destination, whether that was on foot, in a car or by plane. One cannot remember accidents that fortunately did not happen. The endless waiting, often for days, for travel permits, for buses, planes, lorries or even porters is, of course, no longer worth mentioning in retrospect – although this was often one of the most exhausting and nerve-wracking parts of a journey.

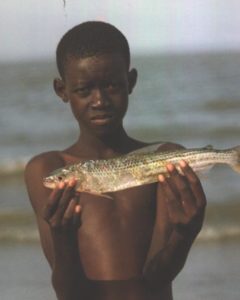

Due to my job, I was very often travelling by plane, with scheduled flights from Switzerland to Africa (to Congo, Sudan, Kenya, South Africa, Botswana, Ghana) or to Asia (Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Thailand, Indonesia), and with small, twin-engine planes (especially in South Sudan).

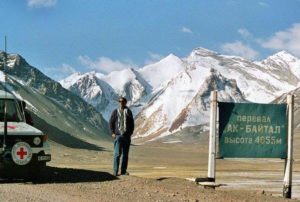

In the plane, you feel completely powerless – because you are not a pilot. I did fall 100 metres into a hole in the air once (in Tajikistan) and zigzagged between lightning bolts and through black clouds (also in Tajikistan), I often came under fire during the war and was often shaken violently during the unsafe landing on bumpy grass fields, but fortunately I never crashed. I was worried and sometimes even scared by the many cows on the grass runways in South Sudan, which made a landing impossible, or in Central Asia by the rusty planes in which other passengers either didn’t want to get on or immediately wanted to get off again, or by the planes completely overcrowded with soldiers and loaded with paraffin barrels during the civil war in South Sudan; often the planes were far too heavy to be able to take off and then crashed in forests or on rocks. Only funny in retrospect is the memory of a young woman in the seat next to me who – on a regularly scheduled flight – out of sheer fear of crashing thought she was only safe on my knees and clung to me in panic for half an hour as if I were her life preserver.

My travels in Europe were limited to train journeys, first to northern Germany (as a child to the North Sea), to England (as a secondary school student with my friend Marco Torriani), to the north to Sweden and Norway, and later to Paris.

During my many journeys in the car, I would often be very lucky. I described one of these incidents in my narrative from Central Asia, “Every Step an Adventure”:

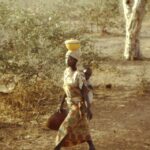

Among the countless, sometimes amusing stories I remember from our adventurous journeys through rough terrain are the two little women from the Murle tribe, stinking of cow dung, who carried heavy pots filled to the brim with milk on their heads; in order to shorten the arduous long journey to the next village by two hours, we had invited them to climb into our Landcruiser and come along; but after only a few minutes they screamed and asked for permission to get out again: the milk had sloshed out of the pots and over their bodies at every pothole.

There are too many car journeys to remember them all, but subsequent journeys – for very different reasons – will certainly stick in my memory for a long time:

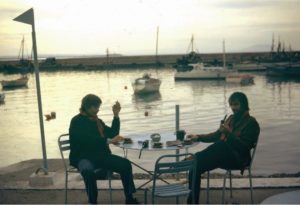

- The wonderful excursions as a student in Provence

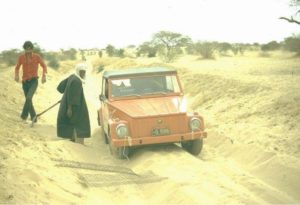

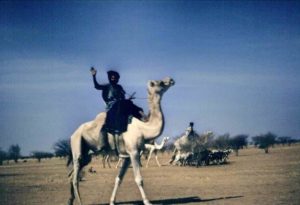

- The journeys in the rainforest of the Congo Kinshasa (during my work as a literature professor 1969-71), so the journey from Kisangani eastwards to Burundi, Tanzania (with a visit to my childhood friend Hanspeter Dänzer in Tanga), Kenya and Uganda. (1970), and the long journey from Kisangani (Congo) northwards through Congo, Central Africa, Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, Niger and Algeria from there by ship to Marseille) in the company of my best Swiss friend Andreas Auer.

- The journey in Bangladesh from Chittagong to Cox Bazar and that to the border of Bangladesh with Burma in the Chittagong Hilltracks (with a visit to the Chakma people).

- The trip with Andreas Auer and Beby Ramanisa to the fishing village of Malvan (near Goa) on the Indian Ocean.

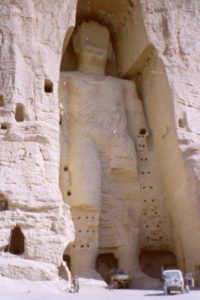

- The many journeys criss-crossing Afghanistan and the five countries of Central Asia, especially the long journey from Dushanbe in Tajikistan through the Pamirs to Khorog and from there to Osh and Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan.

- The trips in America (with Andreas and Beby Auer) in California and (with my friend Beckry Abdel Magid on the Mississipi) in Winona (Minnesota).

- The many trips in Africa during my research time in Sudan and South Sudan, and especially the

- unforgettable three-week expedition in a Landrover from Davos to South Sudan, (through Egypt and the desert to Khartoum accompanied by my father Paul Perner).

- Because of its dangerousness, the journey in the ICRC Landcruiser from Dolisie nan the border with Gabon in Congo-Brazzaville (with the doctor Brigitte Braendli) also remains unforgettable to me,

as well as

- the many trips from Nairobi to Lokichokio and from Lokichokio to Lake Turkana.

In 2021, I briefly summarised my long life as a “death-defying driver” in a letter to the Graubünden Road Traffic Office, to which I voluntarily returned my driving licence – due to my declining eyesight; the Road Traffic Office probably felt somewhat taken off guard by this detailed letter but thanked me by return of post and in a very friendly manner.