IV. A LIFE AS A RESEARCHER

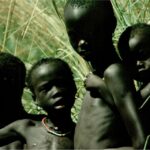

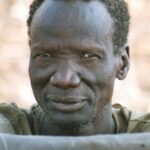

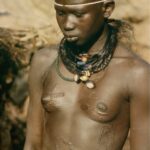

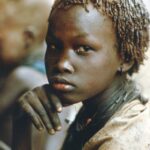

Research among the Anyuak

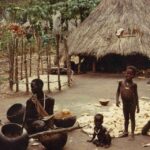

The main work of my research among the Anyuak people, written in English, is entitled “The Anyuak: Living on Earth and in the Sky”. It is the result of five years of fieldwork in the Anyuak country in eastern South Sudan, spanning eight years. The monograph was published in eight volumes by two Basel publishers (Helbing&Lichtenhahn and Schwabe) between 1995 and 2016. On 1225 pages there are 2700 photographs, illustrations, genealogies, historical documents, drawings, graphic representations, a unique, detailed map, an overview of the material culture of the Anyuak people; inserted in the monograph are numerous myths, songs and stories (the oral literature) as well as a CD with tape recordings of music, dance and songs.

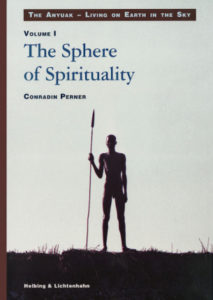

- Vol. I “The Sphere of Spirituality“ ISBN 63-7965-1270-4 *(277p. with 62 pictures) 1994

- Vol. II The Human Territory“ ISBN 63-7965-1271-2 * (305p.with 131 pictures, a map and an overwiew of seasons) 1996 published by Helbing & Lichtenhahn Verlag, Basel in 1994 and 1996; the remaining 6 volumes published by Schwabe-Verlag, Basel

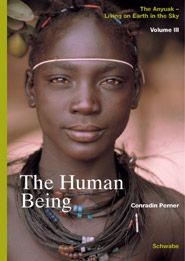

- Vol. III “The Human Being” ISBN 3-7965-1272-0* (317p. with 109 pictures tables etc.) 2003

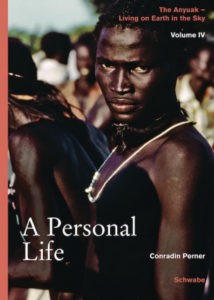

- Vol. IV “A personal Life” (From Birth to Death and Eternity) ISBN 978-3-7965-2227-7 (359p.,150 pictures and a music-CD) 2011

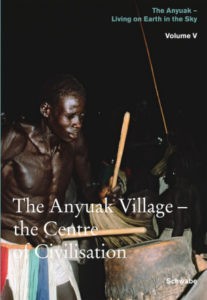

- Vol. V “The Anyuak Village – Centre of Civilisation” (on Social Structures and Justice) ISBN 978-3-7965-3402-73211-5* (359p., 180 pictures, genealogies etc.) 2014

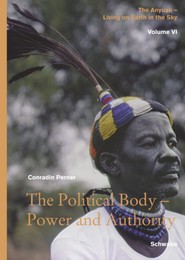

- Vol. VI “The Political Body: Power and Authority” ISBN 978-3-7965-3402-7 (408p., genealogies and 180 pictures,)ISBN 3-7965-1272-0* (317p. with 109 pictures tables etc.) 2015

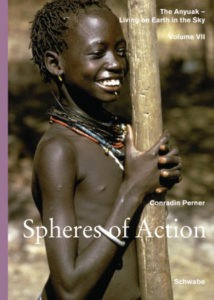

- Vol. VII “Spheres of Action: Economics / Art” ISBN 978-3-7965-3465-2, (285 p., 289 pictures (some in colour) and a summary of activities) 2016

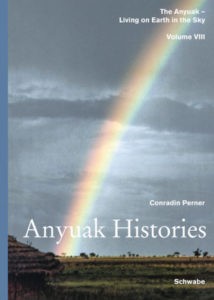

- Vol. VIII “Anyuak Histories”(with a Bibliography) ISBN 978-3-7965-3552-9, (380 p. and 115 pictures) 2016

Information about the course of the research and the personality of the researcher can be found in the book “Why Did You Come If You Leave Again? (published by Xlibris) and in the as yet unpublished “Prologue”.

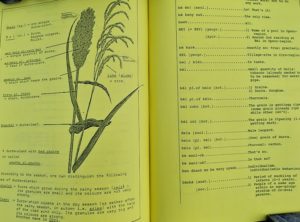

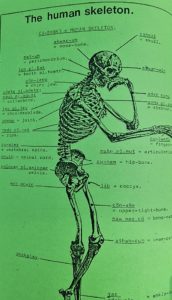

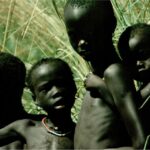

The original aim of my fieldwork among the Anyuak was the study of oral (i.e. unwritten) literature, with tape recordings of myths, stories, songs and historical traditions; the idea of compiling the collected information about the culture of the Anyuak people in a monograph came later, due to the large number of documents and testimonies and pressure from the Anyuak themselves. A prerequisite for studying the oral literature was to understand the language of the people. Learning this language was a great challenge, because there was practically no documentation about the Anyuak language, let alone a dictionary. In the course of my fieldwork, I learned the language and made notes about the vocabulary or even the grammar. I did not want to keep these documents for myself either, but to write them down for the work of future researchers. The resulting dictionary contained 7000 words and terms from all areas, including terms that were by no means known or familiar to all Anyuak. The dictionary had no scientific ambitions, but had been checked for correctness and, where necessary, corrected by one of the greatest connoisseurs of the Anyuak, the Anyuak General Ogut Obang. The dictionary was published in four parts by the American university publisher HRAF (Yale University); it contains a short grammar and a bilingual dictionary (Anyuak/ English and English/Anyuak).

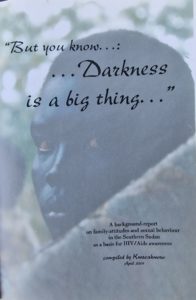

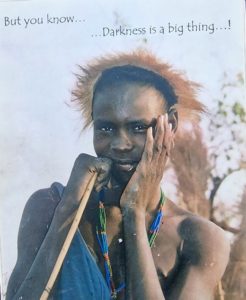

During the two years I worked as a consultant for Unicef (and the 45 aid organisations united in Operation Lifeline Sudan) and for Unesco, I was repeatedly asked to give lectures, organise workshops or prepare expert reports in very different areas. The largest of these studies concerned the sexual behaviour of the South Sudanese and was a preparation for the Unicef campaign against HIV/AIDS. For three months I travelled all over South Sudan and interviewed women and men from different tribes. I summarised the result of this research for Unicef, but I documented the information I received in a 225-page book I called “But you know, Darkness is a big thing...”

(this had been the answer to my question regarding the existence of homosexuality in South Sudan). The book was accompanied by a foreword by the well-known Paris ethnologist Prof. Serge Tornay, and was circulated electronically by Unicef to all aid agencies working in Sudan; it was printed by the ICRC but never published, but can now be read here. The book is one of the best introductions to the self-understanding and knowledge of the South Sudanese, and is not only interesting but also very entertaining.

Readers who would like to broaden and deepen their picture of the inhabitants of South Sudan are referred to some of my other, shorter contributions – a selection is given below:

In 2020, forty years after the end of his research in South Sudan, Kwacakworo made one last trip to the Anyuak. Simona Sabljo, Joane Holliger, Roman Stocker and Napoleon ASdok Gai accompanied him. The unforgettable stay in Kenya and South Sudan was described by Kwacakworo in the report “A trip to Africa in the best company”:

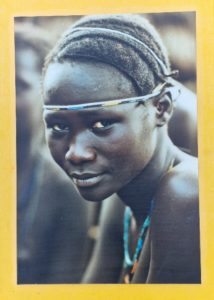

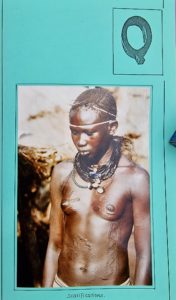

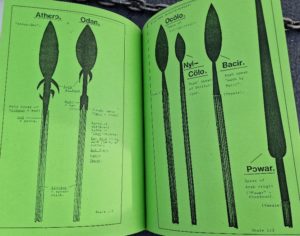

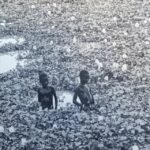

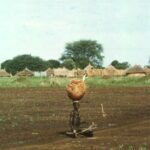

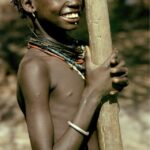

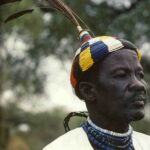

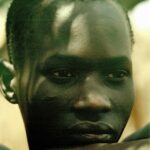

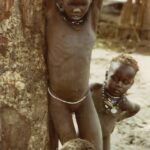

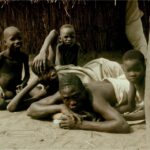

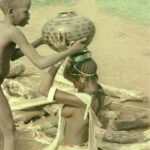

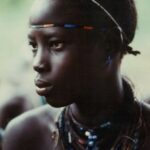

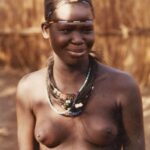

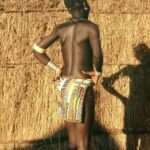

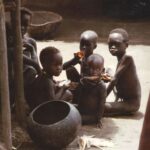

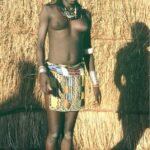

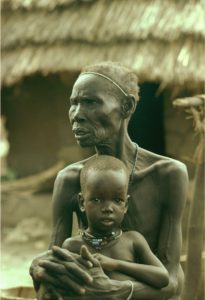

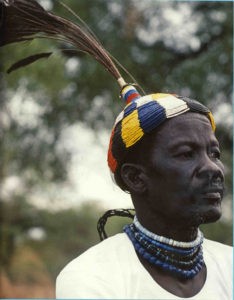

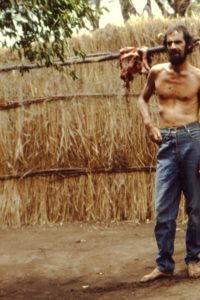

My tasks as an ethnographer also included documentation, i.e. photographic recordings (of people and their economic, social or political activities, their homes, their personal destinies, their festivals and of the landscape in which they live) and tape recordings (on the Kudelski SNN2 professional mini-tape) of music, dance or stories and the collection of everyday objects (pots, spears, beaded jewelry, etc.).

Uncut footage from the Rhaetian Museum. Current exhibitions at https://raetischesmuseum.gr.ch/de/ausstellungen/Seiten/start.aspx

Photos

At that time, of course, there were no digital cameras; I took photos with a big Nikon F3 and used Kodak chrome film (slides). There were many problems with photography; as I only had one camera, I always had to protect it from dirt and water; this was very difficult on the many expeditions through water, mud, in the rain or in great heat, and when trying to survive, there were usually other worries than the condition of my camera. It was also impossible for me to know whether a photo had been taken successfully (or not) – the films had to be developed first. Not only was it impossible to know whether a photograph would meet my expectations (the tension was particularly great in the case of one-off events), it was also impossible to hope that the films I had given to an Anyuak travelling to Malakal had really been posted there (this was not the case with eight films!); the sensitive films would also not survive the humidity or the heat without damage for long. Finally, of course, there was the problem of the individual sensitivities, shyness or fear of the people I had to photograph during their work – not to mention portraits. The Anyuak felt that a photograph would take away a part of themselves and that they would thus lose control over themselves. It was my basic principle not to take pictures without the knowledge of the person(s), didn’t want to get involved in any “looting”. I still think that this principle of respect for another person was good and important for my work and also for my self-respect – although afterwards I also think of those shots that I could have taken – but didn’t; so I don’t have any shots in the intimate and private sphere, no lovers and no family scenes – some would have been very beautiful and touching. Nor did I want to take pictures of violence, prisoners or the submissive behaviour of visitors to the royal court, even if people would not have been bothered or even pleased by this further on. In the course of time, people got used to my activity as a photographer, because it was kept within limits. But when I showed them (and gave them) prints of my photographs after my first return, they were very happy and suddenly all wanted to be photographed.

Tape recordings

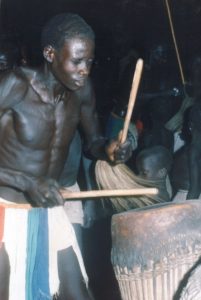

were the prerequisite for my study of oral literature. There should not have been any practical problems, because my tape recorder needed very little battery power (rewinding and fast-forwarding had to be done by hand with a crank); but the tapes were extremely sensitive to moisture and the recorder itself constantly changed speed and became slow (later the Kudelski company would provide me with a device with which I could adjust the speed). Only on the occasion of festivals and drum dances were the recordings spontaneous; stories were mostly told at my home (and by men). I could not verify the myth that only grandmothers tell fairy tales to children – I was not sitting in other people’s huts in the evening or at night and therefore could not verify this aspect of family life. When telling stories, there were always other people listening; therefore it was often difficult to get the silence necessary for good recordings; children showed little ear for such needs. Thanks to the high quality of the recordings, songs and chants were later released as a CD and included in my monograph.

I have given the originals of my photographs and tape recordings (including the equipment) to the ethnographic museum of the University of Zurich for safekeeping.

Ethnographic collection

In order to comprehensively document the material culture of the Anyuak people, I tried to acquire as many utensils used in daily life as possible. Actual “works of art” were not found, or only in the making and beauty of the objects, be they drums, pots, spears, tools or whatever. What was not material (such as body or hair ornaments) or what could not be taken away (such as huts or the important royal regalia) was documented photographically. In the course of the research years, the collection grew, but some of the collected objects were unfortunately also stolen (such as a spear made at my request from sharp giraffe bones in the old style) or fell victim to fire. It was difficult to carry the collected objects for days through the wilderness, then to drive them on a truck to Khartoum and finally to fly them to Switzerland. Fortunately, the ethnographic museum in Geneva had taken an interest in this collection. At the request of the museum curator Claude Savary, I wrote an article that would also make me known among Swiss Africanists in Switzerland:

As I grew older and began to think about my scientific legacy, I came into contact with the Museum of Ethnology (VMZ) of the University of Zurich – thanks to Oswald Iten – and aroused their interest in the objects in Davos, my research documents, voice and music recordings and photographs. The VMZ drew up an inventory and assumed responsibility for my scientific estate. The objects still in the house today were to be stored in the museum only later, i.e. after my death and only in the event that the planned foundation for the preservation of the house did not materialise and the municipality of Davos showed no interest in the house. (The objects mentioned are shown in the 3-dimensional house documentation, see the VMZ website:

In autumn 2022, an exhibition designed by ethnologist Wendelin Kugler will open at the Rhaetian Museum in Chur. For once, the exhibition will not focus on art objects of ethnographic significance, but on the people who collected such objects and brought them to Graubünden. I have promised to be there in Chur and to take this opportunity to read out stories from my research days.

Wendelin Kugler’s interview from 2022 can be heard here: https://vimeo.com/717083159/7724d3e273