V. A LIFE FOR PEOPLE IN NEED

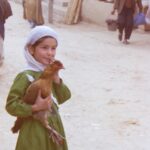

«The misery of the people is really very great». The man who put this sentence at the end of his life story (it was a man from the Anyuak people in South Sudan) was not thinking of warlike conflicts, but merely pondering the fate of all human beings. Yes, it is true that “the misery of the people is really very great”, and this is probably also the reason why so many devout people believe in redemption from their suffering and a better world, possibly even a paradise.

I myself have seen much of this misery in my life and often experienced it first hand, and for me there is no release from the violent images of the past. I have told about it in my stories (for example, the young boy whose face was bitten off by a hyena: ), other memories, however, could not be put into words and remain like shadows, broken pieces or heavy weights in my head, remain indescribable.

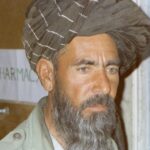

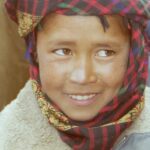

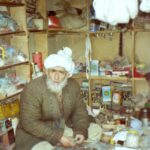

I have spent my whole life in countries where there was war or where the wounds of war had not yet been closed and were still bleeding. As a delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), I worked in Bangladesh, Vietnam, India, Afghanistan, the five countries of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan), Congo-Brazzaville and South Sudan, but the struggle for survival was also felt in places where bombs were not falling and where people were suffering the consequences of destructive wars or famine, drought, floods and disease.

For the ICRC, I worked as a delegate for persecuted people (in Bangladesh), prisoners of war (in India) and cooperation with local aid organisations (in Afghanistan and Central Asia), opened and led various delegations (in South Sudan, in Congo), finally became head of delegation for South Sudan and later advisor to the ICRC for its work in South Sudan.

The story of Napoleon, one of these child soldiers, about his journey from South Sudan to Ethiopia is particularly worth reading;

Because Napoleon and I have developed a close friendly relationship over the years, Davos filmmaker Roman Stocker asked him about his relationship with me during a visit to South Sudan in 2020 and filmed his interview:

I once made a PowerPoint presentation about the ICRC as an aid organisation and my work as a delegate (for a talk in a school):

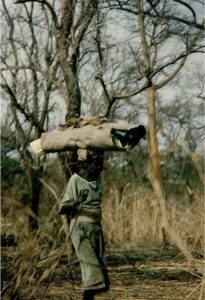

Child soldiers on the run

Child soldiers, as part of the South Sudan Liberation Army, were actually excluded and therefore from ICRC support; only a strictly neutral organisation would be allowed by the warring parties to bring aid to civilians in need. My request to help the child soldiers persecuted by the Ethiopian army was therefore rejected, also with the argument that this would undermine the credibility of the ICRC’s neutrality, provoke a flight ban and thus make it impossible to continue aid to all the other people living in South Sudan; my argument that these were, after all, children in mortal danger was initially not heard; the liberation army should help them (but they were themselves on the run). Thanks to one of my best ICRC friends (from the time in India), Dominique Gross, fortunately then head of the ICRC in Sudan, I was given permission to provide food and water for the child soldiers as they fled and to accompany them on their long march to the refugee camp in Kakuma in Kenya.

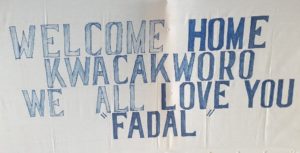

My commitment to these child soldiers made me known as the “Father of the lost boys”.

Help to young South Sudanese

However, my growing reputation as a reliable friend of the South Sudanese also meant that I was repeatedly asked for help privately; I could hardly ever refuse these requests for support (scholarships, help with travel or family problems). In my old age, I would suffer the consequences of my (often gullible) generosity, but I do not regret it: some of the children I supported back then (like Napoleon, for example) made good use of my start-up help and later took on responsibility themselves.

The South Sudanese say they would not say “thank you” (they have no word for it!) but would carry their gratitude in their hearts forever and prove it on occasion. The appointment as honorary citizen of South Sudan on the occasion of the independence celebration in 2011 (and the handing over of the South Sudanese passport eleven years later) shows that such promises were not just empty words and that the South Sudanese – like elephants – do indeed not forget so quickly.