III. A LIFE FOR POETRY, LITERATURE AND LANGUAGE

When one searches for one’s own understanding of life and the reasons for one’s own behaviour, one usually ends up in the distant land of childhood and adolescence. One looks for the reasons that were decisive in the development of one’s personality and steered one’s life in certain directions. Some things, as is well known, were laid in the cradle by one’s ancestors, others probably developed only slowly, in the course of time and on the basis of one’s own concrete experiences and adventures, social circumstances, intellectual possibilities and probably also personal talents. Looking back on my varied curriculum vitae, I too ask myself why I actually became the way I am, where exactly the deep roots of my character might have been and what influences pushed me in this or that direction. Family and nature (i.e. the mountains) may have been the foundation of my life, but I got the spiritual strength, inspiration and foresight I needed for an independent life from books. My father was a reader with a wide range of interests and, had he not been forced to continue his grandfather’s painting business, he would probably have turned to literature and writing. So, we had a lot of books at home, not only literature and biographies but also books on art, history and philosophy; I was allowed to read them at an early age. Later, my father would always give me his “fire brigade money” (that was the pay he received as fire brigade commander for his Sunday picket duty) so that I could buy my own books; I almost always ordered books by (mostly still unknown) Swiss or German poets, often from a bookseller in Germany who sympathised with me.

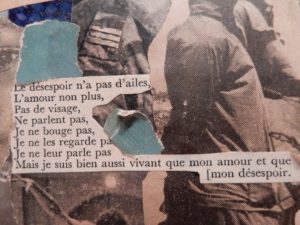

Thus, the wildest adventures during my youth and studies did not take place in the dreamy mountains but in my imaginary world, that is, in my head, in a world without spatial boundaries and without mental limitations: it was books and poems that captivated me from my earliest youth and allowed me to seek out the faraway and to encounter unknown people at close quarters in a foreign emotional world; reading books and poems became exciting journeys of discovery into foreign cultures and human abysses, into highs and lows, into the far reaches and beyond my horizon, into a world full of feelings and experiences. Books became my drug, they made me a rebel and taught me intellectual rebellion. Even before I had read Camus and Sartre, I had become an existentialist. But books often also made me confident and cheerful; poems in particular gave me the courage not to despair of myself and to believe in the good in people. Books were my life, there was nothing else and nothing better – except in the mountains.

Fairy tales were probably at the beginning of my reading addiction, and perhaps it was here that I learned to fear cruelty, violence and evil people. At the age of eight I began to read so-called juvenile books, first (of course!) those by Karl May; my sister, who was four years older, received them first and then handed them over to me – I still own twenty of these books! With Karl May, you could travel to faraway countries and experience many adventures – whether the information was true to reality or made up didn’t matter to me. But what still fascinates me about Karl May was his ability to describe very different landscapes and cultures without ever having been there himself. For me, writing would be the opposite; I could only narrate and describe what I had seen with my own eyes and physically experienced. I could not invent stories, i.e. write novels, or at least I only tried to do so in my early youth (when I had experienced little of substance myself). However, I did not lack imagination; I had inherited plenty of it from my mother.

My “literary career” began when I entered college: From here on, my desire to read overflowed; I read early in the morning, during the day and especially at night, at home or – while waiting for the deer to appear or the first sounds of the birds – early in the morning in forests. Reading books became a constant challenge to my intellectual abilities; books seduced me into worlds I really should not have entered at such a young age, but they sharpened my senses, challenged my mind, heightened my poetic sensibility and at the same time improved my feeling for language. My first language experience was a book by Adalbert Stifter; which I had been given (after breaking my leg on the Bühlenberg in April 1956) by my then German teacher in hospital. During my first years at college, I read books by German, Swiss and American writers (Henry Miller included!), after that I was mainly interested in French writers, – Albert Camus above all. The focus of my literary passion, however, was poetry (the Suhrkamp publishing house published translations of the “poetry” of great poets from all over the world at that time). Among these poets was one from Sweden, Gunnar Ekelöf; I loved his poems so much that I decided to learn Swedish.

First, however, Albert Camus would lure me to France and encourage me to study French literature. This was only a logical consequence of my development: just as springs become streams and streams ultimately flow into a river, the books of my school days led me directly to the study of literature.

Linked to my love of literature is also my interest in languages and the desire to express my own thoughts, to communicate and to tell stories. So, I started writing from the age of eight, some poems and many letters to my grandparents. I had been allowed to write on an old, huge Olympia typewriter (because of the loud clatter it stood on a 2m thick, dark yellow felt mat) and I used this opportunity as often as I could. I would keep this habit for a lifetime, writing thousands of long love letters, many reports about my travels and my work (be it for the ICRC or for the political department of the Swiss government) and eventually my own books. At night I wrote down my mostly dark thoughts, lit only by flashes of lightning, reflecting on the meaning of life and the futility of my own existence.

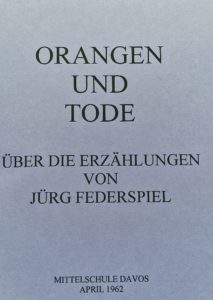

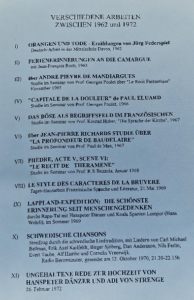

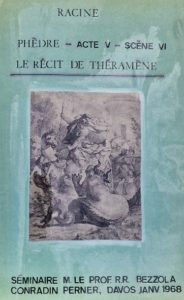

During my time at school I wrote a paper on the Swiss writer Jürg Federspiel (he had lived in our house) and during my studies I wrote about Paul Eluard, Jean-Pierre Richard, André Pieyre de Mandiargues and Jean Racine’s “Phèdre” (the latter received an honorary prize from the University of Zurich) and wrote (with Prof. Paul de Man) a doctoral thesis on the Swedish poet Gunnar Ekelöf; the book “Gunnar Ekelöf’s Night on the Horizon” was published in 1974 by the Swiss Society for Scandinavian Studies as volume 2 of the series “Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie”.

The NZZ published a full-page article on Gunnar Ekelöf’s poems in 1971.

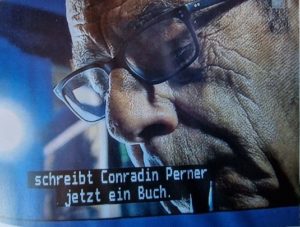

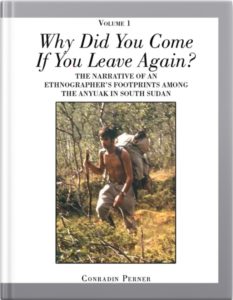

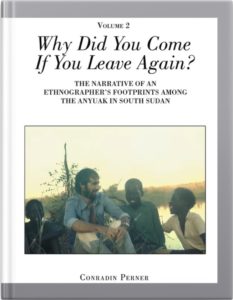

Writing has remained my main my main occupation. From an early age, I wrote every day, wrote articles, wrote long letters or worked on reports, lectures or scientific books. During the first years, literature, then ethnology and finally peacebuilding were at the centre of my work. When writing, it was always important to me to remain as comprehensible as possible, not to bore and to put a lot of thoughtfulness and poetry between the lines; the deeper meaning should be discovered by the reader himself in the underground of the stories. This effort for comprehensibility is even evident in my ethnographic writings, where I have tried to make it easier for the non-academically trained reader to access the findings of my ethnographic research. Because ethnography is ethnology and should lead to a greater understanding of human beings, I also understood my very realistic monograph on the Anyuak people as a contribution to the fight against racial prejudice and to peace between cultures. For me, my research should also have a positive social impact.

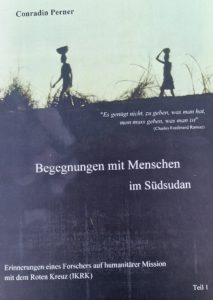

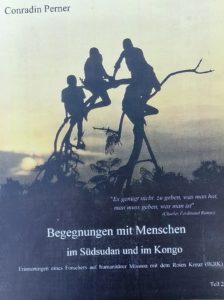

A survey of my various writings may bear witness to the diversity of my various humanitarian, ethnological, literary and other personal interests during my active lifetime:

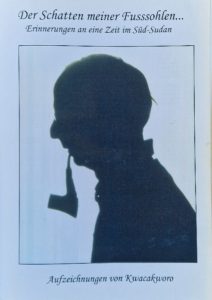

Apart from my eight-volume ethnographic research “The Anyuak: Living on Earth in the Sky” (2592 pages, 1200 pictures, map and CD), a dictionary (“Anyuak, a Luo-language from Southern Sudan” 746p., 1990) and the 2017 autobiography “Why Did You Come If You Leave Again?” (799 pages with photos) I did not publish myself. Perhaps the more than fifteen years of work on the long-running publication of my research in South Sudan had exhausted me mentally and physically; perhaps I simply lacked the desire to have to personally convince publishers of the value of my work. Thus, both the slightly philosophical story collection “Der Schatten meiner Fusssohlen” (The Shadow of the Soles of My Feet) written in the 1990s (26 texts on 229 pages)

as well as my last book “Jeder Schritt ei Abenteuer” (“Every Step an Adventure”)

(three volumes of stories from Africa, Central Asia and Afghanistan) is unpublished, but the stories (not yet corrected!) can be read here Table of contents and stories oft he book (in German) «Jeder Schritt ein Abenteuer»

(Attention! The copyright remains with me and Prof. Beckry Abdel Magid); some of these stories I have read – in German! – aloud.

Listen to them on …