VI. A LIFE FOR PEACE BETWEEN CULTURES

Individual personalities can set a lot in motion, for good or for bad, in science, in politics or in the everyday coexistence of people. Once upon a time – for example – there was a tireless thinker named Josef Bucher, a Swiss ambassador in Nairobi, who was actually responsible for the countries of East Africa and yet also dealt with the causes of the war in Sudan, Kenya’s northern neighbour. In Nairobi, many Sudanese politicians were passing through and often visited the Swiss Embassy on such occasions: the conversation then naturally always concerned the war(s) in Sudan, be it in the Nuba Mountains, in South Sudan or also in Darfur. The Swiss ambassador racked his brains looking for solutions to the conflicts, and because he was very prudent, he also looked for people who could help him with his plans. At some point, he came across the name Kwacakworo, a Swiss from Davos, who was apparently very popular in Sudan and had a good reputation among all the tribes. So one day I was invited to the Swiss Embassy and asked if I could imagine working for Switzerland as a peace advisor. This meeting became the beginning of a very successful and pleasant cooperation with Josef Bucher in his new function as Swiss Special Envoy for Peace Work in Sudan.

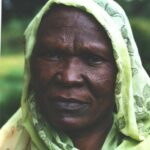

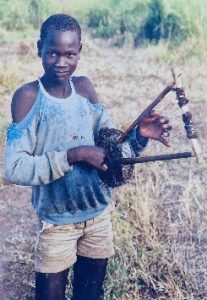

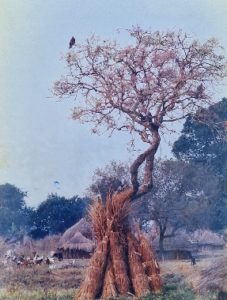

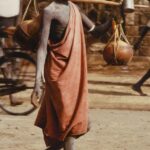

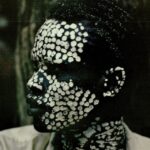

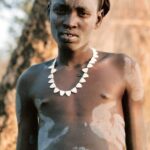

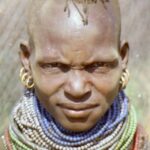

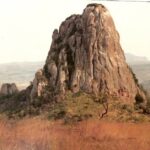

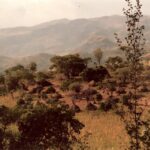

One conflict that preoccupied Ambassador Bucher was the military clashes in the Nuba Mountains. The Nuba belonged oppressed ethnic groups, humiliated and exploited by the government in Sudan; the Nuba fought back, founded their own army and allied themselves with the SPLA liberation army, which in turn fought for the independence of Southern Sudan. Switzerland (with Ambassador Bucher) tried to mediate and, together with the USA, organised a peace conference on the Bürgenstock in January 2002. The conference ended with the decision to send an international peacekeeping force (called the Joint Military Commission) to the Nuba Mountains with the task of disentangling the two warring parties and protecting the civilian population from attacks. I was invited to participate in the conference but declined; I had never been to the Nuba Mountains and knew no one there, so I could neither give advice nor make suggestions. But when I was asked if I would be willing to be part of a peacekeeping mission, I agreed and travelled to Norway for training; the peacekeeping mission was in fact under Norwegian leadership, with General Wilhelmsen as commander. At the conference, four sector commanders were chosen, myself as commander in the Kauda region occupied by the liberation army. For seven months, I therefore lived in the rebel sector of the Nuba Mountains, installed a military station there and travelled all over the country, on foot, by car or by helicopter. The stay allowed me to get to know the Nuba Mountains and made me a confidant of the local SPLA leaders and a close friend of many Nuba people – probably because I had shown great personal interest in Nuba life, had started research, written analyses and developed (for UNESCO) projects to preserve Nuba culture.

The time in the Nuba Mountains is one of the best and most impressive memories from my time in Sudan. The Nuba are warm and very loving people; I would have wished to be able to free them forever from the oppression of foreign, racist governments and to see them happy.

Unfortunately, the Nuba have not benefited from the liberation of South Sudan, even though the Nuba fighters in particular had distinguished themselves through great bravery in the Sudanese civil war. Thus, the war in the Nuba Mountains continues to this day.

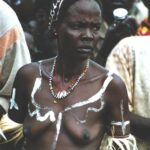

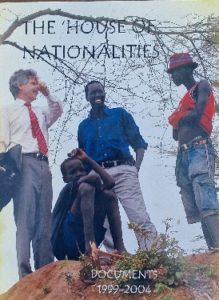

The Nuba were basically a peaceful people and there were no wars among their numerous tribes. The Nuba fought against the government in Northern Sudan, for their land, their dignity and their human rights. The Liberation Army of Southern Sudan was also fighting against the government in the north of the country, but at the same time, the almost one hundred tribes in the south were divided among themselves; tribal fighting not only caused great suffering among the population, but also weakened the strength of the Liberation Army. Peace conferences between the tribes did take place, but the peace agreed upon never lasted long; old, unresolved problems always led to new tribal wars. In search of a political solution, Ambassador Bucher invited representatives of opposing political groups to Aberdare in Kenya. The participants were all quarrelsome intellectuals who had contributed a lot to the unrest in the country through their inflammatory speeches. The ambassador himself did not attend the conference because there was the fear that the discussions between the hostile South Sudanese might degenerate into violence, but sent me to the conference as the only foreigner. The discussions were led by Willy Mutunga, a well-known human rights activist from Kenya. The three-day seminar was peaceful and ended with the proposal to establish an institution that would unite all the tribes of Southern Sudan and where practical problems could be solved peacefully through dialogue. This became the beginning of a large-scale, eight-year peace programme, financially supported by Switzerland and led by Ambassador Josef Bucher (and later by his successor Ambassador Daniel Bieler) with their assistant Salman Bal in Bern.

The “House of Nationalities” programme was multi-faceted and consisted of

- an information brochure and an information sheet

- Five founding conferences in different states of Southern Sudan, with representatives (kings, chiefs, religious leaders, women) of all tribes living in the respective state. The remaining five states were supposed to meet the following year to establish their own “House of Nationalities”; this did not happen because Switzerland withdrew and left the responsibility for the peace project to the provisional government of Southern Sudan.

- An orientation trip for selected tribal leaders and government representatives to countries (South Africa, Botswana and Ghana) where there is peace between ethnic groups.

- A multi-year SDC scholarship programme for young people from areas where there was no access to schools (in order to participate in discussions at all, the tribal representatives in the forum would have to speak at least one commonly known language – in some places there was no school at all!)

- An internet programme for the diaspora. The idea came from Napoleon, who founded, inspired and ran the website “Gurtong” for many years. This kind of communication was fundamentally important for peace in South Sudan, because the South Sudanese living in the diaspora were constantly pouring oil on the blazing fire of tribal feuds; through a factual, non-emotional discussion on the website, more objectivity and mutual respect should be brought into the disputes.

- The creation of an overview of the many tribes located in South Sudan, some of which were still little known. This comprehensive work was published on Gurtong.

While the Swiss ambassador Bucher organised the big conferences abroad, I was responsible for organising the conferences in South Sudan. The two Swiss ambassadors, Josef Bucher and Daniel Bieler, gave me great freedom in my work, but I also received great understanding for the often delicate administrative problems from the embassy secretary in Nairobi, Nicole Wasem, and in Bern from those responsible for the financial side of the programme, Nicole Schneider and Lucette Recordon.

In order to document the work on the “House of Nationalities” for the Swiss government, I wrote annual reports during my work as a peace advisor, filled with documents and my own comments; there are a total of twelve books about 6cm thick. The five tribal conferences were also documented, with pictures of the participating tribal representatives (six volumes).

The House of Nationalities project was conceived as a purely political project to resolve conflicts between the different ethnic groups. That it could be important not only to solve conflicts but also to prevent them, i.e. to bring the different cultures closer to each other without there being a dispute between them. So I worked out a project that was completely focused on the mutual understanding of different cultures and that could have prevented many conflicts through cooperation between these cultures. After all, many tribal wars were also based on a total ignorance of each other’s culture. I was convinced that greater knowledge of a foreign culture would also lead to greater understanding and respect. When I was a consultant for Unicef in Lokichokio, Kenya, I invited prominent representatives of different, hostile tribes to several days of workshops to exchange cultural information and saw that greater knowledge of the foreign can lead to understanding, peace and even friendship.

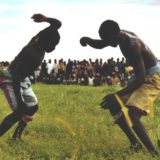

My concept was comprehensive: In Ramciel, a village belonging to the small Atuot tribe in the geographical centre of South Sudan – a large cultural centre was to be built, with a museum, a kind of “village” consisting of inhabited traditionally built houses of all ethnic groups living in South Sudan, with a library, an institute for music and a study and research centre where teachers would be taught about the different cultures of Southern Sudan, a training centre for women, a peace institute and finally a large sports centre where top athletes would be able to train; in the centre of the settlement there would be a large square with a grandstand where cultural events of various kinds could be held (music, folklore, dance, theatre, etc.). ), but it would also be used for sports events (athletics, football, wrestling, etc.). In this cultural centre there would of course also be a school for the children living in the “village”, as well as accommodation for visitors, restaurants, a clinic, etc. The cultural centre would also be used as a centre for the arts. The cultural centre would also be interesting for tourists, as it would allow them to make a stopover in Ramciel on their way from the Nile 30 km away in the east to the national park 30 km away in the west, and to gain an insight into all the cultures of Southern Sudan – and perhaps even to attend events.

Such a comprehensive project would of course have to be financed, but with the help of all aid organisations (such as Unicef, Unesco, WFP, sports associations and universities) this would have been quite possible at the time; the idea that all nations could each support one of the hundred ethnic groups (in building houses in the village, etc.) would not only have been interesting, but also realistic. Unfortunately, the Swiss diplomats were not interested in my project ,although the political leadership of South Sudan was enthusiastic about the project and even willing to give up their own plan of building a museum in Juba) the idea of conflict prevention unfortunately did not find support.

The detailed project can be viewed here:

Huamn Rights

My commitment to human rights actually began with my work for the International Committee of the Red Cross. In my discussions with government representatives, warlords and prison governors, I was always concerned with the rights of the injured, prisoners, displaced persons and refugees as guaranteed by the Geneva Conventions: The idea that the helpless should also be granted a right to human dignity was not always self-evident to everyone.

My commitment to human rights has always been of a practical nature: if you want to make a difference and change things for the better, you have to be committed to it, not just theoretically. “You don’t have to give what you have; you have to give what you are“, the Swiss poet Charles Ferdinand Ramuz had written, and this was probably my personal attitude to life throughout my life (and perhaps the reason why I was always respected).

Working for the Red Cross, but especially the House of Nationalities programme, gave me the opportunity to stand up for human rights, for people’s dignity and their right to be respected by others. In addition to the practical activities mentioned above, I have also repeatedly fought for the principle of human dignity in articles and speeches, for example at a meeting of African human rights organisations in Nairobi.

or on the UN World Day of Peace in Geneva:

What will ultimately remain of my work as a peace counsellor, I do not know. Man seeks strife and war so that he can thirst for harmony and peace. But perhaps I have left seeds in the hearts of the South Sudanese that will eventually take root and blossom.

I can only hope that my message for peace among cultures and their people will not be forgotten, and that there will finally be justice and peace on earth.